Interview with James Brubaker

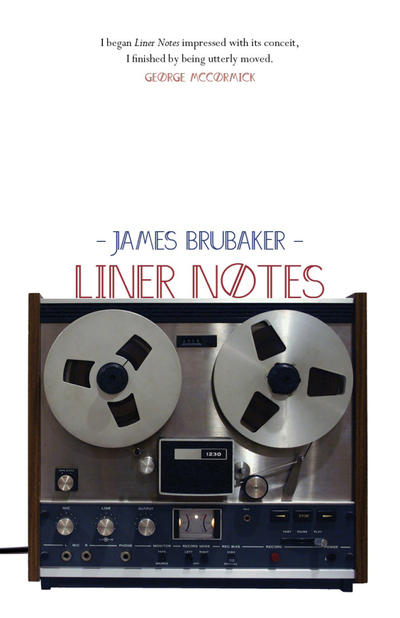

James Brubaker is from Dayton, Ohio, originally, but now teaches and lives in Missouri. He is the author of one book of short stories, Liner Notes (Subito Press), a short volume of pilot episodes for fictional television shows, Pilot Season (Sunnyoutside Press), Black Magic Death Sphere: (Science) Fictions (which won the 2014 Pressgang Prize and will be published in 2015), and a number of short stories that have appeared online and in print. James is also associate editor of The Collapsar, and served as music section editor of The Fiddleback for that journal’s entire run (2010-2013). In 2013 James received his Ph.D. in English, with an emphasis in Fiction Writing, from Oklahoma State University. He is currently hard at work on a novel without a name.

Can you say a few words about your creative process, the experience of writing and publishing, and how your book came to fruition?

Liner Notes grew very directly out of my time in the Ph.D. program at Oklahoma State University. Before going there, I primarily wanted to write novels, but the emphasis at Oklahoma State, at the time, anyway, was on the short story. In my first workshop there, I wrote some stories I didn’t love, and then then in my second workshop, hit a hot streak writing stories where music played a significant role (these were early versions of the stories “Oh Yoko” and “Of Muscle Memory”). Since I had a dissertation looming a few years away, and I knew it would be a collection of stories, I decided to start writing stories towards different ways of thinking about music. This has shaped my creative process a great deal, as I’ve gotten in the habit of thinking about what a book will look like early in the writing process, and then writing towards a specific idea or set of ideas. My other books, Pilot Season, and Black Magic Death Sphere: (Science) Fictions (which will come out in late 2015), were both written in similar ways, as a series of experiments and exercises orbiting a central idea (television culture for the first, and pop sci-fi tropes for the second). In writing the stories, there’s a lot of trial and error. All three manuscripts ended up with a bunch of stories that were abandoned at various points in the writing process as I realized they either weren’t working, or weren’t working for that particular project. It’s kind of fun because then I end up with some extra stories to back into after a book is done and try to hammer into shape. As for publishing, I sent a lot of stories to a lot of places and racked up a ton of rejections for a long time. Eventually, a few stories started to sneak through the slush piles and found homes, and it’s gotten a little easier since. I submitted and/or queries Liner Notes to at least seventy presses, contests, and agents before it won Subito’s Prize for Prose. Black Magic Death Sphere was only sent to about seventeen before it found a home.

When did you first identify yourself as a writer?

This is a tricky question. I first identified myself as a writer when I was an undergraduate. But I wasn’t a very good writer, and for much of that time, I didn’t have the dedication to really do the things I imagined myself doing. At that point, I liked the idea of being a writer more than the idea of actually writing. It wasn’t until I finished my bachelor’s degree and decided not to pursue work teaching high school, right away, that I started really writing. For about a year after finishing my degree, I worked as a barista at the old Borders in Dayton and wrote a novel I’d vaguely started writing when I was student teaching the year before. I’d go to work from 3:30 to 11:30 most nights, then go up to Bill’s Donuts and write and/or hang out with friends until three in the morning, then go home, wake up at one, eat lunch and do the whole thing over again. By the time I started my MA at Wright State, even though I was writing more, and working hard to be a better writer, I had trouble identifying as a writer because I hadn’t had any success and I hated the questions people asked when I said “I’m a writer.” I think as soon as we say “I’m a writer,” people expect the proof. They want to see the books. That sucks, because just the act of seriously writing should be enough, but I was pretty self-conscious about the whole thing. It wasn’t until one of my artist friend’s Seth started introducing me as a writer, and talking about me like a writer that I started to buy into it. Then it got easier still when I started taking workshops at Wright State, and really began to see my work grow and improve while working with Erin Flanagan and Jimmy Chesire, there.

Is there a particular book – or person – who made you want to write?

I wanted to write from a very early age. In first or second grade, I participated in a Cub Scout cake sale where we had to bake cakes, with the help of our parents, of course, themed around what we wanted to be when we grew up. My cake was a pencil because I wanted to be a writer. And then in high school, I got another burst of inspiration from Douglas Coupland’s 90’s output. In college, it was Michael Chabon. But the book that sort of crystallized everything for me and showed me a path that made sense for me as a writer, that felt like the kind of work that I wanted to be writing, and which, I guess, ultimately activated me as a fiction writer was Jorge Luis Borges’s Ficciones. So much of what I’d written up to that point was interested in weird, big ideas and textuality, but I never knew how to really work with those ideas. Borges showed me how.

Looking back on your experience at WSU, was there an individual – or formative experience – that continues to resonate and inform your creative process?

There are two specific experiences I remember, and they both came out of the same workshop, which was taught by Erin Flanagan. The first is that I’d written this baseball story about a kid who played high school baseball and he was doping, with the help of his dad, so that he could make the majors. And it was a pretty solid, but not great story, and Erin kept telling me the end wasn’t right. So I’d try something else and show it to her, and it still wasn’t right, and I think she ended up reading five or six different endings to this story, and I still never got it right. That was fine, and it helped get me beyond the idea that stories were too much like equations—you know, you can’t just keep plugging in new endings until the equation works, necessarily, and that’s what I was doing. It was like I was guessing trying to figure out the right ending. The other was when I workshopped a story called “A New Map of America,” and it was the first story I wrote with footnotes, and I didn’t really know what I was doing with the footnotes, or why they were there. During workshop, Erin commented on how unimportant most of the footnotes were, but how in a couple, we began to see the contours of a relationship between the “writer” of the primary text, and the “editor” who was writing the footnotes. I spent a lot of time rewriting the footnotes so that the real story was in the footnotes, and was more about the friendship between the editor and writer, and less about this bizarre map that the writer was making. It ended up being the first story I had published in a venue not affiliated with a school where I was a student or teacher. It was the second issue of The Cupboard, and it was taken precisely because of how the footnotes worked. They even published it under the fictional writer/mapmakers name, and listed me as the editor. That experience was huge. Through it, I learned a lot about identifying the human, emotional core in work that might read as weird or experimental to others. That’s probably shaped my approach to writing more than any other experience.

What’s the worst writing advice you’ve received?

Always write in the mornings. Outline your stories in advance. Outline nothing and discover the story as you go. Let the characters actions guide the stories. Murder your darlings. Use more interiority to explain everything about a story. Don’t use any interiority at all. Never violate point of view. Don’t worry about point of view. Write what you know. Don’t put yourself in your own stories. Make every sentence a masterpiece. Never submit until you’re 100% certain a story is perfect. Most writing advice is pretty terrible, I think. I like reading about writers’ processes and approach to craft because I always find interesting or helpful ideas, but the minute anyone begins telling someone else the best ways to write, that’s a deal breaker. Do whatever you need to do to write what you want to write. I think the only advice I’ve been given that wasn’t awful was: be healthy and take care of yourself; try to write every day, but don’t beat yourself up if you can’t; always write with an open mind and a full heart; find a place, process, and approach that works for you; send things out when they feel finished, but only after you’ve proofread the “final draft” at least three times; and read everything.

What advice – if any – would you give to aspiring apprentice writers?

Be healthy and take care of yourself. Try to write every day, but don’t beat yourself up if you can’t. Always write with an open mind and a full heart. Find a place, process, and approach that works for you. Send things out when they feel finished, but only after you’ve proofread the “final draft” at least three times. And read everything.

Can you say a few words about literary citizenship and why it’s so important for writers – and readers – to participate?

It’s so important, for both altruistic and pragmatic reasons. I mean, it should be easy for us all to be good literary citizens. We write because we love reading and we love writing and we love interacting with other people who also love those things. If you don’t love all three of those things, you’re probably doing something wrong. The publishing world is drastically changing and has been a bit unstable for a while, so it’s important that we find as much writing and as many writers that we love, as possible, and get excited about them, because that’s going to keep this whole literary nation in which we’re literary citizens afloat. Altruistically, we should just be good literary citizens because it’s the right thing to do, and pragmatically because it keeps the whole enterprise running.

Finally, in the 21st century, what is the artist’s role; or more specifically, do you have a sense of artistic obligation to self and/or others?

My own sense of artistic obligation has a lot to do with empathy. In everything I write, I’m always searching for some sort of strong emotional bond that feels absent, somewhere. I don’t consider what I do to be political, really, in any way, shape or form, but I do feel a sense of obligation to make my work humane, even when it gets dark and gritty, or whatever. At the end of the day, most people are kind of messed up, and damaged, and sad, and it’s all we can do to find ways to work through being those things, and sometimes there’s solace to be found in sharing stories about those things. That’s why, even when I’m—and this gets to the first part of the question—writing to explore the intersection of culture and human experience, which I think is one of the things that I think it’s important for artists to be doing right now, I’m always looking for this strong, human core within that almost critical context.

Where do you see yourself headed as an artist?

I really like the trajectory I’m on. I’ve got my music book, my “sci-fi” book, and my TV chapbook. I’m currently working on a novel, which I’m pretty excited about. The first draft is almost done. And after that, I want to keep pushing myself in writing more stories and novels. I’ve got tons of ideas, and I just want to make sure that I’m always trying new things with my writing, and finding ways to continue growing. The minute writing stops being thrilling and fun, I think I might have trouble thinking of myself as an artist or writer. I want to play more with weird ideas and metafiction and what not, but I also want to write my version of a quiet “literary” novel, to sort of challenge myself since I feel so far removed from that kind of writing.

For additional information on author James Brubaker, please visit his website at http://jamesbrubaker.net/.